Grade 4 Unit 3 Reading History the American Revolution

- This article covers the political aspects of the American Revolution. For the military campaign and notable battles, see American Revolutionary War.

The American Revolution refers to the flow during the last half of the eighteenth century in which the Thirteen Colonies that became the U.s. gained independence from the British Empire.

In this period, the colonies rebelled confronting Great britain and entered into the American Revolutionary War, too referred to (peculiarly in U.k.) as the American War of Independence, between 1775 and 1783. This culminated in the American Announcement of Independence in 1776, and victory on the battlefield in 1781.

France played a cardinal function in aiding the new nation with money and munitions, organizing a coalition against Britain, and sending an army and a fleet that played a decisive office at the battle that effectively concluded the war at Yorktown.

The revolution included a series of broad intellectual and social shifts that occurred in early American guild, such as the new republican ideals that took concur in the American population. In some states sharp political debates broke out over the role of democracy in government. The American shift to republicanism, also as the gradually expanding republic, acquired an upheaval of the traditional social hierarchy, and created the ethic that formed the core of American political values.

The revolutionary era began in 1763, when the armed forces threat to the colonies from France ended. Adopting the view that the colonies should pay a substantial portion of the costs of defending them, Britain imposed a series of taxes that proved highly unpopular and that, by virtue of a lack of elected representation in the governing British Parliament, many colonists considered to be illegal. After protests in Boston the British sent gainsay troops. The Americans mobilized their militia, and fighting bankrupt out in 1775. Loyalists composed about 15-20 percent of the population. Throughout the war the Patriots generally controlled 80-90 percent of the territory, every bit the British could merely hold a few littoral cities. In 1776, representatives of the 13 colonies voted unanimously to prefer a Declaration of Independence, by which they established the The states of America.

Contents

- 1 Origins

- 1.one Taxation without representation

- ane.2 1765: Stamp Deed unites the Colonies in protestation

- 1.3 Boston Massacre and Boston Tea Political party

- 1.4 Liberalism and republicanism

- 1.4.ane Western land dispute

- one.5 Crises, 1772–1775

- 2 Fighting begins at Lexington: 1775

- 3 Factions: Patriots, Loyalists and Neutrals

- 3.1 Patriots - The Revolutionaries

- 3.2 Loyalists and neutrals

- 3.3 Grade differences among the Patriots

- 3.4 Women

- 4 Creating new state constitutions

- 5 Military history: expulsion of the British 1776

- vi Independence, 1776

- 7 War

- seven.1 British return: 1776-1777

- seven.two British attack on the South, 1778-1783

- seven.iii Treason effect

- viii Peace treaty

- 9 Aftermath of war

- 10 National debt

- eleven Worldwide influence

- 11.ane Interpretations

- 12 Notes

- 13 References

- 13.one Surveys

- xiii.2 Specialized studies

- 13.3 Primary sources

- fourteen External links

- 15 Credits

The Americans formed an brotherhood with France in 1778 that evened the war machine and naval strengths. Ii main British armies were captured at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781, leading to peace with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, with the recognition of the United States as an independent nation bounded by British Canada on the north, Spanish Florida on the s, and the Mississippi River on the west.

Origins

Taxation without representation

Before the revolution: The Thirteen Colonies are in pinkish

By 1763, Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland possessed a vast holding on the North American continent. In addition to the 13 colonies, sixteen smaller colonies were ruled directly by majestic governors. Victory in the Seven Years' War had given Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland New France (Canada), Spanish Florida, and the Native American lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1765, the colonists still considered themselves loyal subjects of the British Crown, with the same historic rights and obligations as subjects in Great britain.[1]

The British government sought to revenue enhancement its American possessions, primarily to help pay for its defense of North America from the French in the Seven Years' State of war. The trouble was not that taxes were loftier but that they were not consulted well-nigh the new taxes, as they had no representation in parliament. The phrase "no taxation without representation" became popular inside many American circles. Regime officials in London argued that the Americans were represented "virtually"; but most Americans rejected the theory that men in London, who knew nil almost their needs and conditions, could represent them.[2] [3]

In theory, Great U.k. already regulated the economies of the colonies through the Navigation Acts co-ordinate to the doctrines of mercantilism, which held that anything which benefited the empire (and hurt other empires) was good policy. Widespread evasion of these laws had long been tolerated. Now, through the employ of open up-ended search warrants (Writs of Assistance), strict enforcement became the do. In 1761 Massachusetts lawyer James Otis argued that the writs violated the constitutional rights of the colonists. He lost the case, but John Adams after wrote, "American independence was then and there born."

In 1762, Patrick Henry argued the Parson's Cause in Virginia, where the legislature had passed a law and information technology was vetoed by the King. Henry argued, "that a King, by disallowing Acts of this salutary nature, from being the begetter of his people, degenerated into a Tyrant and forfeits all right to his subjects' obedience."[4]

1765: Postage Deed unites the Colonies in protest

In 1764 Parliament enacted the Saccharide Human activity and the Currency Deed, further vexing the colonists. Protests led to a powerful new weapon, the systemic boycott of British goods. In 1765 the Stamp Deed was the offset straight tax ever levied by Parliament on the colonies. All newspapers, almanacs, pamphlets and official documents—even decks of playing cards—had to have the stamps. All xiii colonies protested vehemently, as pop leaders like Henry in Virginia and Otis in Massachusetts rallied the people in opposition. A hugger-mugger group, the "Sons of Liberty," formed in many towns, threatening violence if anyone sold the stamps. In Boston, the Sons of Liberty burned the records of the vice-admiralty courtroom and looted the elegant dwelling of the chief justice, Thomas Hutchinson.

Several legislatures called for united action, and nine colonies sent delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in New York City in October 1765. Moderates led by John Dickinson drew up a "Annunciation of Rights and Grievances" stating that taxes passed without representation violated ancient rights. Lending weight to the argument was an economic boycott of British merchandise, as imports into the colonies fell from £2,250,000 in 1764 to £ane,944,000 in 1765. In London, the Rockingham authorities came to power and Parliament debated whether to repeal the stamp revenue enhancement or send an army to enforce it. Benjamin Franklin eloquently made the American case, explaining the colonies had spent heavily in manpower, money and claret in defence force of the empire in a series of wars confronting the French and Indians, and that paying further taxes for those wars was unjust and might bring about a rebellion. Parliament agreed and repealed the taxation, but in a "Declaratory Human activity" of March 1766 insisted that parliament retained full ability to make laws for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever."[5]

Boston Massacre and Boston Tea Party

This 1846 lithograph has become a classic paradigm of the Boston Tea Party

In March v, 1770, tensions escalated and five colonists (including Crispus Attucks) were killed in the Boston Massacre. The aforementioned day parliament repealed the Stamp Human activity, and the Declaratory Deed, which asserted England'south control over the colonies was enacted. This deed didn't change anything because England already had full control over the colonies, so this act was ignored by the colonists.

Committees of correspondence were formed in the colonies to coordinate resistance to paying the taxes. In previous years, the colonies had shown niggling inclination towards collective activity. Prime Minister George Grenville'due south policies were bringing them together.[6]

Liberalism and republicanism

John Locke's liberal ideas were very influential; his theory of the "social contract" implied the natural right of the people to overthrow their leaders, should those leaders beguile the historic rights of Englishmen. Historians find little trace of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's influence among the America Revolutionaries.[7] To write the various land and national constitutions, the Americans were influenced instead by Montesquieu's assay of the ideally "balanced" British Constitution.

The motivating strength was the American encompass of a political ideology called "republicanism," which was dominant in the colonies by 1775. It was influenced profoundly by the "country political party" in U.k., whose critique of British government emphasized that political corruption was to exist feared. The colonists associated the "courtroom" with luxury and inherited aristocracy, which Americans increasingly condemned. Corruption was the greatest possible evil, and civic virtue required men to put borough duty ahead of their personal desires. Men had a civic duty to fight for their land. For women, "republican motherhood" became the ideal, as exemplified past Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren; the first duty of the republican adult female was to instill republican values in her children and to avoid luxury and ostentation. The "Founding Fathers" were potent advocates of republicanism, peculiarly Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams.[8]

Western land dispute

The Proclamation of 1763 restricted American motion across the Appalachian Mountains. Yet, groups of settlers continued to motion west. The proclamation was before long modified and was no longer a hindrance to settlement, but its promulgation without consulting Americans angered the colonists. The Quebec Act of 1774 extended Quebec's boundaries to the Ohio River, shutting out the claims of the 13 colonies. By then, however, the Americans had scant regard for new laws from London—they were drilling militia and organizing for war.[9]

Crises, 1772–1775

An American version of London cartoon that denounces the "rape" of Boston in 1774 by the Intolerable Acts

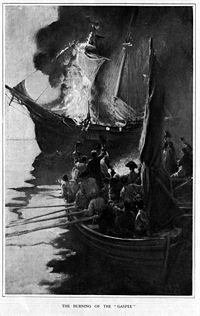

While there were many causes of the American Revolution, it was a series of specific events, or crises, that finally triggered the outbreak of war.[10] In June 1772, in what became known as the Gaspée Affair, a British warship that had been vigorously enforcing unpopular trade regulations was burned by American patriots. Soon afterwards, Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts reported that he and the majestic judges would exist paid direct by London, thus bypassing the colonial legislature. In belatedly 1772, Samuel Adams set about creating new Committees of Correspondence that would link together patriots in all xiii colonies and eventually provide the framework for a insubordinate regime. In early 1773, Virginia, the largest colony, set upward its Committee of Correspondence, including Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson.[11]

The Intolerable Acts included four acts.[12] The first was the Massachusetts Government Human action, which contradistinct the Massachusetts charter, restricting town meetings. The 2nd deed was the Administration of Justice Human action, which ordered that all British soldiers to be tried were to be arraigned in Britain, non the colonies. The third act was the Boston Port Deed, which closed the port of Boston until the British had been compensated for the tea lost in the Boston Tea Political party (the British never received such a payment). The quaternary human activity was the Quartering Act of 1774, which compelled the residents of Boston to house British regulars sent in to control the vicinity. The Outset Continental Congress endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, which declared the Intolerable Acts to exist unconstitutional, called for the people to form militias, and called for Massachusetts to form a Patriot regime.

In response, primarily to the Massachusetts Government Human activity, the people of Worcester, Massachusetts set up an armed lookout man line in front end of the local courthouse, refusing to allow the British magistrates to enter. Similar events occurred, soon afterwards, all across the colony. British troops were sent from England, but by the fourth dimension they arrived, the entire colony of Massachusetts, with the exception of the heavily garrisoned city of Boston, had thrown off British control of local diplomacy.

Fighting begins at Lexington: 1775

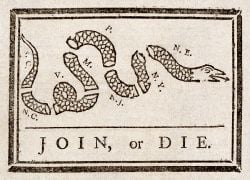

"Join, or Die" by Benjamin Franklin was recycled to encourage the former colonies to unite confronting British rule

The Battle of Lexington and Concord took place April 19, 1775, when the British sent a regiment to confiscate arms and arrest revolutionaries in Hold, Massachusetts. It was the outset fighting of the American Revolutionary War, and immediately the news aroused the 13 colonies to call out their militias and ship troops to congregate Boston. The Boxing of Bunker Loma followed on June 17, 1775. By tardily spring 1776, with George Washington as commander, the Americans forced the British to evacuate Boston. The patriots were in control everywhere in the xiii colonies and were ready to declare independence. While there even so were many loyalists, they were no longer in command anywhere by July 1776, and all of the British Majestic officials had fled.[xiii]

The 2d Continental Congress convened in 1775, after the war had started. The Congress created the Continental Army and extended the Olive Branch Petition to the crown as an attempt at reconciliation. King George III refused to receive information technology, issuing instead the Proclamation of Rebellion, requiring activeness against the "traitors." There would be no negotiations whatsoever until 1783.

Factions: Patriots, Loyalists and Neutrals

Patriots - The Revolutionaries

The revolutionaries were called Patriots, Whigs, Congress-men, or Americans during the War. They included a full range of social and economic classes, just a unanimity regarding the need to defend the rights of Americans. Subsequently the war, political differences emerged. Patriots such every bit George Washington, James Madison, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay for example, were deeply devoted to republicanism while also eager to build a rich and powerful nation, while patriots such every bit Patrick Henry, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson represented democratic impulses and the agrarian plantation element that wanted a localized gild with greater political equality.

Loyalists and neutrals

While there is no way of knowing the bodily numbers, historians estimate 15 to 25 percentage of the colonists remained loyal to the British Crown; these became known every bit "loyalists" (or "Tories," or "Rex's men"). Loyalists were typically older, less willing to interruption with quondam loyalties, often continued to the Anglican church, and included many established merchants with business organisation connections beyond the empire, for instance Thomas Hutchinson of Boston. Contempo immigrants who had not been fully Americanized were also inclined to support the king, such as recent Scottish settlers in the back state; among the more than striking examples of this, meet Flora Macdonald.[fourteen]

Native Americans generally rejected American pleas that they remain neutral. About groups aligned themselves with the empire. In that location were as well incentives provided by both sides that helped to secure the affiliations of regional peoples and leaders; the tribes that depended well-nigh heavily upon colonial trade tended to side with the revolutionaries, though political factors were important equally well. The most prominent Native American leader siding with the loyalists was Joseph Brant of the Mohawk nation, who led borderland raids on isolated settlements in Pennsylvania and New York until an American ground forces nether John Sullivan secured New York in 1779, forcing all the loyalist Indians permanently into Canada.[15]

A minority of uncertain size tried to stay neutral in the war. Nigh kept a low contour. However, the Quakers, especially in Pennsylvania, were the most important grouping that was outspoken for neutrality. As patriots declared independence, the Quakers, who continued to practise concern with the British, were attacked as supporters of British dominion, "contrivers and authors of seditious publications" disquisitional of the revolutionary cause.

After the state of war, the great majority of loyalists remained in America and resumed normal lives. Some, such as Samuel Seabury, became prominent American leaders. A minority of about fifty,000 to 75,000 Loyalists relocated to Canada, Uk or the West Indies. When the Loyalists left the South in 1783, they took nigh 75,000 of their slaves with them to the British West Indies.[sixteen]

Class differences among the Patriots

Historians, such every bit J. Franklin Jameson in the early twentieth century, examined the form composition of the patriot cause, looking for evidence that there was a class war inside the revolution. In the last 50 years, historians have largely abandoned that estimation, emphasizing instead the high level of ideological unity. Just equally there were rich and poor Loyalists, the patriots were a "mixed lot" with the richer and better educated more probable to become officers in the army. Ideological demands always came starting time: the patriots viewed independence as a means of freeing themselves from British oppression and revenue enhancement and, above all, reasserting what they considered to be their rights. Most yeomen farmers, craftsmen and small merchants joined the patriot cause as well, demanding more than political equality. They were particularly successful in Pennsylvania but less so in New England, where John Adams attacked Thomas Paine's Common Sense for the "absurd democratical notions" information technology proposed.[17] [18]

Women

The cold-shoulder of British goods involved the willing participation of American women; the boycotted items were largely household items such as tea and cloth. Women had to return to spinning and weaving—skills that had fallen into disuse. In 1769, the women of Boston produced xl,000 skeins of yarn, and 180 women in Middletown, Massachusetts, wove 20,522 yards of textile.[19] [twenty]

Creating new state constitutions

By summer 1776, the patriots had command of all the territory and population; the loyalists were powerless. All thirteen colonies had overthrown their existing governments, closing courts and driving British agents and governors from their homes. They had elected conventions and "legislatures" that existed outside of any legal framework; new constitutions were needed in each state to replace the superseded royal charters. They were states now, not colonies.[21] [22]

On January v, 1776, New Hampshire ratified the beginning land constitution, six months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. And then, in May 1776, Congress voted to suppress all forms of crown authority, to be replaced by locally created dominance. Virginia, Southward Carolina, and New Jersey created their constitutions before July 4. Rhode Island and Connecticut simply took their existing purple charters and deleted all references to the crown.[23]

The new states had to decide non only what class of government to create, they starting time had to decide how to select those who would craft the constitutions and how the resulting document would be ratified. States in which the wealthy exerted business firm control over the procedure, such as Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, New York and Massachusetts, created constitutions that featured:

- Substantial property qualifications for voting and even more substantial requirements for elected positions (though New York and Maryland lowered holding qualifications)[24]

- Bicameral legislatures, with the upper house as a check on the lower

- Strong governors, with veto ability over the legislature and substantial appointment authority

- Few or no restraints on individuals holding multiple positions in government

- The continuation of land-established religion

In states where the less flush had organized sufficiently to accept significant power—especially Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New Hampshire—the resulting constitutions embodied:

- universal white manhood suffrage, or minimal property requirements for voting or holding role (New Jersey enfranchised some property owning widows, a step that it retracted 25 years later)

- strong, unicameral legislatures

- relatively weak governors, without veto powers, and little appointing authorization

- prohibition against individuals holding multiple authorities posts

The results of these initial constitutions were past no means rigidly fixed. The more populist provisions of Pennsylvania's constitution lasted but 14 years. In 1790, conservatives gained power in the country legislature, called a new ramble convention, and rewrote the constitution. The new constitution essentially reduced universal white-male person suffrage, gave the governor veto power and patronage appointment authority, and added an upper house with substantial wealth qualifications to the unicameral legislature. Thomas Paine called it a constitution unworthy of America.[25]

Military history: expulsion of the British 1776

The military history of the war in 1775 focused on Boston, held by the British but surrounded by militia from nearby colonies. The Congress selected George Washington as commander-in-main, and he forced the British to evacuate the city in March 1776. At that bespeak the patriots controlled virtually all of the 13 colonies and were ready to consider independence.[26]

Independence, 1776

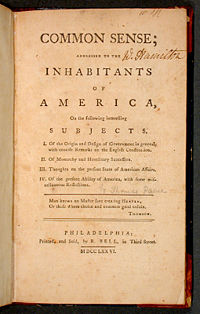

Mutual Sense by Thomas Paine

On January 10, 1776, Thomas Paine published a political pamphlet entitled Mutual Sense arguing that the only solution to the problems with Britain was republicanism and independence from Great britain.[27]

On July iv, 1776, the Proclamation of Independence was ratified by the 2d Continental Congress. The war began in April 1775, while the declaration was issued in July 1776. Until this signal, the colonies sought favorable peace terms; now all the states called for independence.[28]

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Matrimony, usually known as the Articles of Confederation, formed the first governing document of the United states of america of America, combining the colonies into a loose confederation of sovereign states. The 2nd Continental Congress adopted the articles in November 1777.[29]

War

British render: 1776-1777

The British returned in force in August 1776, engaging the fledgling Continental Ground forces for the starting time time in the largest activity of the Revolution in the Battle of Long Island. They eventually seized New York City and near captured General Washington. They made the city their primary political and military base, holding information technology until 1783. They likewise held New Jersey, but in a surprise set on, Washington crossed the Delaware River into New Jersey and defeated British armies at Trenton and Princeton, thereby reviving the patriot cause and regaining New Jersey.

In 1777, the British launched ii uncoordinated attacks. The army based in New York Metropolis defeated Washington and captured the national capital at Philadelphia. Simultaneously, a 2nd army invaded from Canada with the goal of cutting off New England. It was trapped and captured at Saratoga, New York, in October 1777. The victory encouraged the French to officially enter the war, as Benjamin Franklin negotiated a permanent military alliance in early on 1778. Later Espana (in 1779) and the Dutch became allies of the French, leaving Britain to fight a major war alone without major allies. The American theater thus became only 1 front in Britain'southward war.[thirty] [31]

Because of the alliance and the deteriorating military situation, Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, evacuated Philadelphia to reinforce New York City. General Washington attempted to intercept the retreating column, resulting in the Battle of Monmouth Courtroom Business firm, the last major battle fought in the northern states. Later an inconclusive engagement, the British successfully retreated to New York City. The northern war afterwards became a stalemate, every bit the focus of attention shifted to the southern theatre.[32]

British set on on the South, 1778-1783

The siege of Yorktown ended with the surrender of a British army, paving the way for the end of the American Revolutionary War

In tardily December 1778, the British captured Savannah, Georgia, and started moving north into South Carolina. Northern Georgia was spared occupation during this time flow, due to the Patriots victory at the Battle of Kettle Creek in Wilkes County, Georgia. The British moved on to capture Charleston, South Carolina, setting up a network of forts inland, believing the loyalists would rally to the flag. Not enough loyalists turned out, however, and the British had to fight their way due north into North Carolina and Virginia, where they expected to exist rescued by the British armada.

That armada was defeated by a French fleet, however. Trapped at Yorktown, Virginia, the British surrendered their main gainsay army to General Washington in October 1781. Although King George Three wanted to fight on, his supporters lost command of Parliament, and the war effectively ended for America.[33] A finale naval boxing was fought past Helm John Barry and his coiffure of the Alliance every bit three British warships led by the HMS Sybil tried to have the payroll of the Continental Army on March 10, 1783, off the coast of Greatcoat Canaveral.

Treason event

In Baronial 1775 the king declared Americans in artillery to be traitors to the Crown. The British regime at starting time started treating American prisoners as common criminals. They were thrown into jail and preparations were made to bring them to trial for treason. Lord Germain and Lord Sandwich were peculiarly eager to do so. Many of the prisoners taken past the British at Bunker Loma evidently expected to be hanged, merely the authorities declined to have the next footstep: treason trials and executions. There were tens of thousands of loyalists under American control who would take been at risk for treason trials of their ain (past the Americans), and the British built much of their strategy effectually using these loyalists. After the surrender at Saratoga in 1777, there were thousands of British prisoners in American hands who were effectively hostages. Therefore no American prisoners were put on trial for treason, and although most were badly treated, eventually they were technically accorded the rights of belligerents. In 1782, past act of Parliament, they were officially recognized as prisoners of war rather than traitors. At the end of the war both sides released their prisoners.[34]

Peace treaty

The peace treaty with Britain, known as the Treaty of Paris (1783), gave the U.Due south. all land east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes. The Native Americans living in this region were not a party to this treaty and did non recognize it until they were defeated militarily by the United States. Issues regarding boundaries and debts were not resolved until the Jay Treaty of 1795.[35]

Backwash of state of war

For two percent of the inhabitants of the United States, defeat was followed by exile. Approximately sixty thousand of the loyalists were left the newly-founded republic, most settling in the remaining British colonies in Northward America, such as the Province of Quebec (concentrating in the Eastern Townships), Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia. The new colonies of Upper Canada (now Ontario) and New Brunswick were created past Britain for their do good.[36]

National debt

The national debt after the American Revolution fell into three categories. The get-go was the $11 one thousand thousand owed to foreigners—by and large debts to France. The 2nd and third—roughly $24 one thousand thousand each—were debts owed past the national and land governments to Americans who had sold nutrient, horses and supplies to the revolutionary forces. Congress agreed that the power and the authority of the new government would pay for the foreign debts. There were too other debts that consisted of promissory notes issued during the Revolutionary War to soldiers, merchants, and farmers who accustomed these payments on the premise that the new Constitution would create a government that would pay these debts somewhen.

The war expenses of the private states added upwardly to $114,000,000, compared to $37 million past the fundamental government.[37] In 1790, Congress combined the state debts with the strange and domestic debts into one national debt totaling $eighty one thousand thousand. Everyone received face value for wartime certificates, so that the national honour would be sustained and the national credit established.

Worldwide influence

The most radical touch on was the sense that all men have an equal voice in government and that inherited status carried no political weight in the new republic.[38] The rights of the people were incorporated into country constitutions. Thus came the widespread exclamation of liberty, private rights, equality and hostility toward corruption which would evidence core values of republicanism to Americans. The American shift to republicanism, too every bit the gradually expanding democracy, caused an upheaval of the traditional social hierarchy, and created the ethic that formed the core of American political values.[39] [40]

The greatest challenge to the old society in Europe was the challenge to inherited political power and the autonomous idea that authorities rests on the consent of the governed. The example of the first successful revolution against a European empire provided a model for many other colonial peoples who realized that they too could break away and go self-governing nations.[41]

The American Revolution was the get-go wave of the Atlantic Revolutions that took concord in the French Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, and the Latin American wars of liberation. Aftershocks reached Ireland in the 1798 rising, in the Polish-Lithuanian Democracy, and in the Netherlands.[42]

The Revolution had a stiff, immediate impact in Great britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, and France. Many British and Irish Whigs spoke in favor of the American crusade. The Revolution was the first lesson in overthrowing an old government for many Europeans who after were agile during the era of the French Revolution, such as the Marquis de Lafayette. The American Proclamation of Independence had some impact on the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789.[43] [44]

Instead of writing essays that the mutual people had the right to overthrow unjust governments, the Americans acted and succeeded. The American Revolution was a case of practical success, which provided the rest of the world with a 'working model'. American republicanism played a crucial part in the development of European liberalism, as noted by the great German historian Leopold von Ranke in 1848:

By abandoning English constitutionalism and creating a new republic based on the rights of the individual, the North Americans introduced a new force in the globe. Ideas spread most quickly when they have found adequate concrete expression. Thus republicanism entered our Romantic/Germanic world.... Up to this signal, the conviction had prevailed in Europe that monarchy best served the interests of the nation. Now the thought spread that the nation should govern itself. Just only after a land had actually been formed on the footing of the theory of representation did the full significance of this idea become clear. All after revolutionary movements have this same goal…. This was the complete reversal of a principle. Until then, a king who ruled past the grace of God had been the middle around which everything turned. Now the thought emerged that ability should come up from below.... These 2 principles are similar two opposite poles, and information technology is the conflict between them that determines the course of the mod globe. In Europe the disharmonize between them had non all the same taken on concrete course; with the French Revolution it did.[45]

Nowhere was the influence of the American Revolution more profound than in Latin America, where American writings and the model of colonies, which actually broke complimentary and thrived decisively, shaped their struggle for independence. Historians of Latin America have identified many links to the U.S. model.[46]

Despite its success, the Due north American states' new-found independence from the British Empire allowed slavery to continue in the U.s. until 1865, long after information technology was banned in all British colonies.

Interpretations

Interpretations about the issue of the revolution vary. At one cease of the spectrum is the older view that the American Revolution was not "revolutionary" at all, that it did not radically transform colonial guild just simply replaced a distant authorities with a local one.[47] A more recent view pioneered by historians such every bit Bernard Bailyn, Gordon Due south. Wood and Edmund Morgan is that the American Revolution was a unique and radical result that produced deep changes and had a profound impact on world diplomacy, based on an increasing belief in the principles of republicanism, such as peoples' natural rights, and a system of laws called past the people.[48]

Notes

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. xi.

- ↑ William S. Carpenter, "Taxation Without Representation" in Dictionary of American History, vol. vii, edited by Thomas C. Coc and Harold W. Chase (New York: Charles Scribner'south Sons, 1976, ASIN B000LVZRWE).

- ↑ John C. Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (Boston: Trivial, Brown and Visitor, 1943). Bachelor online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ Miller 1943.

- ↑ Miller 1943.

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 11.

- ↑ Charles W. Toth (ed.), Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite: The American Revolution & the European Response (Troy, NY: The Whitston Publishing Company, 1989), p. 26. Bachelor online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 9.

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. xv.

- ↑ Miller 1943, 335-392.

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 22-24.

- ↑ Miller 1943, 353-376.

- ↑ John C. Miller, Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1948), p. 87. Available online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ Robert M. Calhoon, "Loyalism and Neutrality," in Greene and Pole 1994.

- ↑ Gary B. Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America (New York: Viking Developed, 2005, ISBN 0670034207).

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 20-22.

- ↑ Nash 2005.

- ↑ John Phillips Resch, and Walter Sargent (eds.), War And Club in the American Revolution: Mobilization And Home Fronts (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois Academy Press, 2006, ISBN 0875806147).

- ↑ Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence (New York: Vintage Books, 2006, ISBN 1400075327).

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 41.

- ↑ Allan Nevins, The American States During and After the Revolution, 1775-1789 (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1927). Available online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 29.

- ↑ Nevins 1927.

- ↑ Nevins 1927; Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 29.

- ↑ Forest 1992

- ↑ Piers Mackesy, The War for America: 1775-1783 (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Printing, 1992). Available online. Retrieved Baronial 15, 2007.

- ↑ Greene and Pole 1994, chap. 26.

- ↑ Greene and Pole 1994, chap. 27.

- ↑ Greene and Pole 1994, chap. 30.

- ↑ Mackesy 1992.

- ↑ Don Higginbotham, The War of American Independence: Armed services Attitudes, Policies, and Practise, 1763-1789 (Boston: Northeastern Academy Press, 1983, ISBN 0930350448).

- ↑ Mackesy 1992; Higginbotham 1983.

- ↑ Mackesy 1992; Higginbotham 1983.

- ↑ Miller 1948, 166.

- ↑ Miller 1948, 616-648.

- ↑ Claude Halstead Van Tyne, The Loyalists in the American Revolution (New York: The Macmillan Visitor, 1902).

- ↑ Merrill Jensen, The New Nation (New York: Vintage Books, 1950), p. 379.

- ↑ Woods 1992.

- ↑ Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992, ISBN 0679404937).

- ↑ Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole (eds.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1994, ISBN 1557865477), chap. lxx.

- ↑ Robert R. Palmer, The Historic period of the Democratic Revolution: Vol. I: The Challenge (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 1959) (New edition, 1969, ISBN 0691005699). Available online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ Palmer 1959; Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 53-55.

- ↑ Palmer 1959; Greene & Pole 1994, chap. 49-52.

- ↑ Lynn Hunt and Jack Censer, Chapter 3 Folio 1: Enlightenment and Man Rights, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, Heart for History and New Media (George Stonemason University) and the American Social History Project (City University of New York). Retrieved August fifteen, 2007.

- ↑ Quoted in Jürgen Heideking and James A. Henretta (eds.), Republicanism and Liberalism in America and the German States, 1750-1850 (New York: Cambridge University Printing, 2002, ISBN 0521800668), p. 128.

- ↑ Meet John Lynch, "The Origins of Castilian American Independence," in Cambridge History of Latin America, vol. 3, edited past Leslie Bethell (New York: Cambridge University Printing, 1985, ISBN 0521232244), pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Jack Greene, "The American Revolution," The American Historical Review 105(i). Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ Gordon South. Wood, The American Revolution: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2002, ISBN 0679640576).

References

ISBN links back up NWE through referral fees

- Barnes, Ian, and Charles Royster. The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution. New York: Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0415922437

- Boatner, Mark Mayo. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1974 (original 1966). ISBN 0811705781

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson (eds.). The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Armed services History (5-Volume Set). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 1851094083

- Greene, Jack P. and J. R. Pole (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1557865477

- Purcell, L. Edward. Who Was Who in the American Revolution. New York: Facts on File, 1993. ISBN 0816021074

- Resch, John P. (ed.). Americans at War: Society, Culture and the Homefront. New York: MacMillan Reference Books, 2004. ISBN 002865806X

Surveys

- Cogliano, Francis D. Revolutionary America, 1763-1815; A Political History. London: Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0415180589

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: War machine Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763-1789. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1983. ISBN 0930350448

- Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution 1763-1776. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 2004 (original 1968). ISBN 0872207056

- Jensen, Merrill. The New Nation. New York: Vintage Books, 1950. Reprint edition, 1966. New York: Random House. ISBN 0394705270

- Lecky, William Edward Hartpole. The American Revolution, 1763-1783. New York: D. Appleton, 1898. Available online. Retrieved August xv, 2007.

- Mackesy, Piers. The War for America: 1775-1783. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1992. Available online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Crusade: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1985. ISBN 0195035755. Available online. Retrieved August fifteen, 2007.

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783. Boston: Little, Brown and Visitor, 1948. Available online. Retrieved August fifteen, 2007.

- Miller, John C. Origins of the American Revolution (Boston: Petty, Brown and Company, 1943). Bachelor online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- Wood, Gordon Due south. The American Revolution: A History. New York: Modern Library, 2002. ISBN 0679640576

- Wrong, George M. Washington and His Comrades in Artillery: A Relate of the State of war of Independence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1921. Bachelor online. Retrieved Baronial 15, 2007.

Specialized studies

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Printing of Harvard University Printing, 1972 (original 1967). ISBN 0674443012

- Becker, Carl Lotus. The Declaration of Independence: A Report on the History of Political Ideas. (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1922). Available online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- Berkin, Ballad. Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence. New York: Vintage Books, 2006. ISBN 1400075327

- Breen, T. H. The Market place of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 2004. ISBN 019518131X

- Crow, Jeffrey J. and Larry E. Tise (eds.). The Southern Experience in the American Revolution. Chapel Colina: University of Northward Carolina Press, 1978. ISBN 0807813133

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0195170342

- Freeman, Douglas Southall. Washington: An Abridgement. Edited by Richard Harwell. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1968. ASIN B000OUSPMQ

- Kerber, Linda Grand. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. Chapel Loma, NC: The Academy of North Carolina Press, 1980. ISBN 0807814407

- McCullough, David. 1776. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0743226712

- Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Nascency of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. New York: Viking Adult, 2005. ISBN 0670034207

- Nevins, Allan. The American States During and Subsequently the Revolution, 1775-1789. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1927). Available online. Retrieved August xv, 2007.

- Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996 (original 1980). ISBN 0801483476

- Palmer, Robert R. The Historic period of the Democratic Revolution: Vol. I: The Challenge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Printing, 1959 (New edition, 1969, ISBN 0691005699). Bachelor online. Retrieved Baronial xv, 2007.

- Resch, John Phillips and Walter Sargent (eds.). War And Society in the American Revolution: Mobilization And Home Fronts. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2006. ISBN 0875806147

- Rothbard, Murray. Conceived in Liberty (4 Volume Ready). Auburn, AL: Ludwig Von Mises Institute, 1999. ISBN 0945466269

- Shankman, Andrew. Crucible of American Democracy: The Struggle to Fuse Egalitarianism and Capitalism in Jeffersonian Pennsylvania. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2004. ISBN 0700613048

- Volo, James M. and Dorothy Denneen Volo. Daily Life during the American Revolution. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 0313318441

- Woods, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992. ISBN 0679404937

Primary sources

- Commager, Henry Steele and Richard B. Morris (eds.). The Spirit of 'Lxx-Six: The Story of the American Revolution Equally Told by Participants. New York: Da Capo Press, 1995 (original 1975, 1958). ISBN 0306806207

- Humphrey, Carol Sue (ed.). The Revolutionary Era: Primary Documents on Events from 1776 to 1800. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 0313320837

- Morison, Samuel Eastward. (ed.). Sources and Documents Illustrating the American Revolution, 1764-1788, and the Germination of the Federal Constitution. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1965 (original 1923). ISBN 0195002628

- Rhodehamel, John H. (ed). The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence. New York: Library of America, 2001. ISBN 1883011914

- Tansill, Charles C. (ed.). Documents Illustrative of the Germination of the Union of the American States. Washington, DC: Govt. Print. Office, 1927. Bachelor online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved May 17, 2021.

- Library of Congress Guide to the American Revolution

- Liberty! The American Revolution – PBS Boob tube Series

- The American Revolution.org

- American Independence Museum

Credits

New Earth Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This commodity abides by terms of the Creative Eatables CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-past-sa), which may exist used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due nether the terms of this license that tin can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a listing of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- American_Revolution history

The history of this article since it was imported to New Earth Encyclopedia:

- History of "American Revolution"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to apply of individual images which are separately licensed.

davenportwhictime.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/American_Revolution

Publicar un comentario for "Grade 4 Unit 3 Reading History the American Revolution"